| TINTIN LANGUAGES | |

| AFRIKAANS | |

| ALGUERES | |

| ALSATIAN | |

| ARABIC | |

| ASTURIAN | |

| BASQUE | |

| BERNESE | |

| BENGALI | |

| BRETON | |

| BULGARE | |

| CAMBODIAN | |

| CATALAN | |

| CHINESE | |

| CORSICAN | |

| CZECH | |

| DANISH | |

| DUTCH | |

| ENGLISH | |

| ESPERANTO | |

| FARSI | |

| FAEROESE | |

| FINNISH | |

| FRENCH | |

| FRIESIAN | |

| GALICIAN | |

| GALLO | |

| GAUMIAN | |

| GERMAN | |

| GREEK | |

| HEBREW | |

| HUNGARIAN | |

| ICELANDIC | |

| INDONESIAN | |

| ITALIAN | |

| JAPANESE | |

| KOREAN | |

| LATIN | |

| LUXEMBOURGER | |

| MALAYALAM | |

| NORWEGIAN | |

| OCCITAN | |

| PICARDY | |

| POLISH | |

| PORTUGUESE | |

| ROMANSCH | |

| RUSSIAN | |

| SERBO-CROAT | |

| SINHALESE | |

| SLOVAK | |

| SPANISH | |

| SWEDISH | |

| TAHITIAN | |

| TAIWANESE | |

| THAI | |

| TIBETAN | |

| TURKISH | |

| VIETNAMESE | |

| WELSH | |

| TOTAL 60 VERIFIED LANGUAGES | |

| RUMOURS | |

| MIRANDES | |

|

MONEGASCO |

|

| PROVENÇAL | |

| RUANDES | |

| MONEGASCO | |

| LINKS | CRAB MENÚ | CASTAFIORE MENU |

WANTED¡¡ |

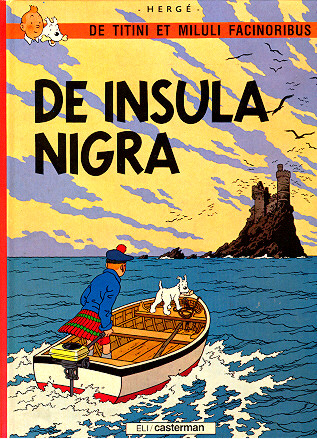

LATIN | |||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

Latin was brought to

the Italian peninsula by a wave of immigrants from the north about

1000 B.C. Over the centuries the city of Rome rose to a position

of prominence and the Latin of Rome became the literary standard

of the newly-emerging Roman Empire. Side by side with classical

Latin a spoken vernacular developed, which was carried by the

Roman army throughout the empire. It completely displaced the

pre-Roman tongues of Italy, Gaul, and Spain and was readily

accepted by the barbarians who partitioned the Roman Empire in the

5th century A.D. Further divisions led to the eventual emergence

of the modern Romance languages—Italian, French, Spanish,

Portuguese, and Rumanian.

The Latin, or Roman, alphabet was created in the 7th century B.C. It was based on the Etruscan alphabet, which in turn was derived from the Greek. Of the original twenty-six Etruscan letters the Romans adopted twenty-one. The original Latin alphabet was A, B, C (which stood for both g and k), D, E, F, I (the Greek zeta), H, I (which stood for both i and j), K, L, M, N, 0, P, Q, R (though for a long time this was written P), S, T, V (which stood for u, v, and w), and X. Later the Greek zeta (I) was dropped and a new letter G was placed in its position. After the conquest of Greece in the first century B.C. the letters Y and Z were adopted from the contemporary Greek alphabet and placed at the end. Thus the new Latin alphabet contained twenty-three letters. It was not until the Middle Ages that the letter J (to distinguish it from I) and the letters U and W (to distinguish them from V) were added. Latin lacks somewhat the variety and flexibility of Greek, perhaps reflecting the practical nature of the Roman people, who were more concerned with government and empire than with speculative thought and poetic imagery. Yet in the hands of the great masters of the classical period it was the vehicle for a body of literature and poetry that can bear comparison with any in the world.

|

|

PUBLISHER ELI / Casterman

|

|

ONLINE SHOPING |

|

LINKS

|

|

|

I'VE GOT THIS ONE | ! WANTED! |