| TINTIN LANGUAGES | |

| AFRIKAANS | |

| ALGUERES | |

| ALSATIAN | |

| ARABIC | |

| ASTURIAN | |

| BASQUE | |

| BERNESE | |

| BENGALI | |

| BRETON | |

| BULGARE | |

| CAMBODIAN | |

| CATALAN | |

| CHINESE | |

| CORSICAN | |

| CZECH | |

| DANISH | |

| DUTCH | |

| ENGLISH | |

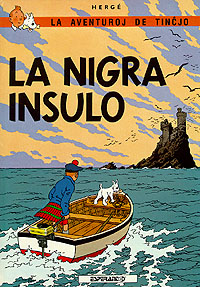

| ESPERANTO | |

| FARSI | |

| FAEROESE | |

| FINNISH | |

| FRENCH | |

| FRIESIAN | |

| GALICIAN | |

| GALLO | |

| GAUMIAN | |

| GERMAN | |

| GREEK | |

| HEBREW | |

| HUNGARIAN | |

| ICELANDIC | |

| INDONESIAN | |

| ITALIAN | |

| JAPANESE | |

| KOREAN | |

| LATIN | |

| LUXEMBOURGER | |

| MALAYALAM | |

| NORWEGIAN | |

| OCCITAN | |

| PICARDY | |

| POLISH | |

| PORTUGUESE | |

| ROMANSCH | |

| RUSSIAN | |

| SERBO-CROAT | |

| SINHALESE | |

| SLOVAK | |

| SPANISH | |

| SWEDISH | |

| TAIWANESE | |

| THAI | |

| TIBETAN | |

| TURKISH | |

| VIETNAMESE | |

| WELSH | |

| TOTAL 60 VERIFIED LANGUAGES | |

| RUMOURS | |

| MIRANDES | |

|

MONEGASCO |

|

| PROVENÇAL | |

| RUANDES | |

| MONEGASCO | |

| LINKS | CRAB MENÚ | CASTAFIORE MENU |

|

ESPERANTO | |||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

Esperanto, the most important and influential of the so-called artificial languages, was devised in 1887 by Dr. Lazarus Ludwig Zamenhof of Warsaw, Poland. Based on the elements of the foremost Western languages, Esperanto is incomparably easier to master than any national tongue, for its grammar rules are completely consistent, and a relatively small number of basic roots can be expanded into an extensive vocabulary by means of numerous prefixes, suffixes, and infixes. The French Academy of Sciences has called Esperanto "a masterpiece of logic and simplicity."

|

|

PUBLISHER |

|

ONLINE SHOPING |

| LINKS |

PUBLISHED BY ESPERANTIX

PUBLISHED BY ESPERANTIX

P.B. 40 F-75721 Paris Cedex France

|

|

I'VE GOT THIS ONE | ! WANTED! |